| The Grand Rapids Press | Thursday, May 9, 1999 |

by Terry Finch Hamilton Grand Rapids Press The Earth is crafted from an Amana refrigerator box, but that makes the lesson in this play no less powerful. As the ancient Aztec story goes, people used to work and play in harmony. They shared. They were kind. They respected each other. But then things went sour. People began lying. Stealing. Fighting. Hating. The world was falling apart, and two third graders in a West Side school gym practicing their school play hold their heads in their hands, devastated. The lesson is so simple, 8 year olds are teaching it: If we can't all get along, we're doomed. As our country still reels from the horror that kids are killing each other based on alienation and hate, children in a school on Lexington Ave. NW are learning lessons of acceptance and respect. |

|

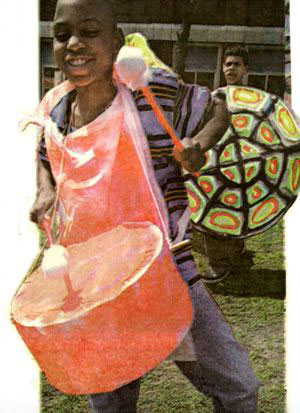

| The method seems like mayhem. They scamper like woodland animals. They twist and twirl like

a raging volcanic eruption. They become gods of sun and wind. They're acting out stories that are centuries old,

passed on from generation to generation of Aztecs and Anishinabek Indians. Throughout the school, kids chant a

mantra that's become as ingrained in them as after-school TV: "Honesty. Kindness. Sharing. Respect." The 235 students at Academia de Espanol - the Grand Rapids School District's Spanish immersion school - will present "Power of Place", a celebration of art, music, dance and drama at 9:45 a.m. Wednesday at the Van Andel Museum Center. The production is open to the public with museum admission. Every kid has a part, from kindergartners popping like popcorn to sixth graders dramatizing the end of the world. It's the culmination of two months of studying the Aztec and Anishinabek cultures and learning that as different as we human beings all are, we're surprisingly the same. This project was funded with grants from the Michigan Humanities Council, the Arts Council of Greater Grand Rapids and the schools PTA. The school hired Kalamazoo theater artists Irene (Ike) Vasquez and Dan Runyan of Magical Rain Theaterworks to direct the program, with help from the Public Museum of Grand Rapids and Native American Prevention Services. |

|

| Diversity is a part of everyday life here at the Spanish immersion school. At recess, black,

white and Hispanic kids all play basketball together. Kids of all colors mix and meld while learning to understand,

speak, read and write in two languages. But this program goes well beyond "Buenos Dias" to the very core

of being human. "In these ancient stories, the world literally falls apart when people can't get along," says Vasquez, 49, education/artistic coordinator for "Power of Place". "If a kid feels his personal behavior is insignificant, why should he care? |

|

| "We're working from the inside out here", she says. We're not teaching about different

cultures by talking about what the people ate and how they dressed." Instead, these youngsters learn how the

bear, turtle, fish and eagle clans take care of each other, watch out for each other. They learn that each person

in a community has a responsibility to the others. "These are human being lessons," Vasquez says. "In the process, they are learning about themselves," adds Renee Dillard, Anishinabe educator who's been working with the kids. "They're seeing that they're not that different." Before young people can embrace and respect other people, they have to know and respect themselves, these educators say. Vasquez believes that was missing in the misfit Colorado teens who were disturbed enough to murder. "Those kids weren't just alienated from others - they didn't know their own core," Vasquez says. "They had all the material things, but their spirits were starved. A lot of kids today feel that their invisible. Kids need to make themselves real in the world." Dillard sees that all the time in her travels to West Michigan schools. As she teaches kids about the richness of her American Indian culture, she asks them about their own background. What are they? |

|

| Unaware of Heritage I hear a lot of young people say "I'm not anything,'" Dillard says. "That's amazing to me. I always tell them, "Of course you're something.' It's very important that they know that." Vasquez tells kids that, classroom by classroom, as her husband and partner Dan Runyan turns youngsters into corn-carrying ants in the school cafeteria. |

|

| She passes out the makings of Ojos de Dios - Eyes of God - to third graders. The yarn and stick

creations are given to Hispanic children at birth. Every year, a different color string is added to represent a

new stage in the child's life. The kids make their own Ojos de Dios, marking their birth, their first day of school,

the births of siblings. Include your stories, Vasquez urges them. The happy, the hurtful, the sad. There are so many stories in your life, and you don't even think their important, but they are," she tells them. The Ojos de Dios will be the symbols of their life. One boy tells of falling off his bike after another kid dared him to do a risky stunt. He got a big bump on his head, he says. Dillard seizes the moment. "Do you have to do something just because someone dares you?" she asks the kids. Hmmmmmmm. "What would happen if you said no?" Vasquez asks them. Patricia Cross starts flapping her arms like chicken wings. "Bawkbawkbawkbawkbawk," she clucks. Her classmates giggle. And nod. "Well, what's worse?" Vasquez asks them. "A big bump on the head or some teasing words?" |

|

| Common thread More than a dozen kids answer in unison. "Words" they say. Vasquez nods knowingly. "They say sticks and stones can break your bones, but words can never hurt you - but that's not true is it?" she says. "Words can break your heart." |

|

| They talk about how small you feel when someone makes fun of you. Dillard tells of being teased

in school for being Indian. Her long-ago classmates patted their hands over their mouths in war whoops to tease

her, she told the kids. "Indians don't even do that," she says. "That's something Hollywood made

up." "Things that happen to you when you're a kid can stick with you your whole life," says Vasquez, a child of migrant workers who still remembers racist teasing from first grade, 44 years ago in Holland. "When you respect someone, you don't say hurtful words to them." It all makes sense, the kids say. But real life can be tough. "I try to be nice to people, but it's always easy," says 8 year old Ryan VandenAkker, taking a break from morning recess. "Especially in soccer, when the other team is always punching you and scratching and stuff." Ryan plays Waboos the Rabbit in the play, an uppity creature who teases the other animals because his tail is longer and more beautiful than theirs. When the Creator gets wind of his attitude, He trims the bunny's tail to a little white fluff. "You shouldn't tease people if you have something better than they do," Ryan says. "It's hard to respect people who don't respect you," says 10 year old Eric Walcott, who plays the wolf leader of the animal council. "Sometimes I get bullied by other kids. That's hard and frustrating. But I think what we're learning is helping a little bit already." Emily McJones, who plays the alligator who leads the wind god to the sun, says the lessons sink in. "The old stories tell about when the sun was hogging all the color and music in the world," the 12-year-old says. "When the sun finally shared it, he felt better about himself. It's the same with people." Downstairs, Runyan coaches kids through ancient Indian tales of how the Creator meant for us to need each other. How if we don't treat each other with respect and kindness, we'll be destroyed by fire. How if you have enough kindness, respect, honesty and sharing in your own heart, you can afford to give some of it away. The lessons are plastered throughout the school halls: Lo que le haces a otros, regresa hacia ti. What you do to others comes back to you. As he urges sun gods, baby animals, ants and elders through their paces, Runyan notes even the process of the play breeds lessons. "They all have to depend on each other, pay attention to each other, support each other, trust each other," Runyan says. "A very real circle has formed here. There has to be harmony for this to work on stage." Between them, Runyan and Vasquez have spent 35 years using theater, art, myth and mystery in culture workshops throughout the country. They've only been at the Academia de Espanol school for two months. Yet one second-grade girl through her arms around Vasquez the other day. "You're my most favorite teacher," she told her. It makes her beam. "Kids have been more than calling out for help," Vasquez says. "Look at the drug use, the anorexia, the suicide." Dillard has been teaching the kids about the medicine wheel, a symbol of the never-ending cycle of life. It has seven directions: north, south, east, west, up, down. That's six. Every once in a while a kid will get that seventh direction," Dillard says. "Inward." |

|

| Diversity | Emotional Intelligence | Cooperative Learning | Customer Responses | Press |